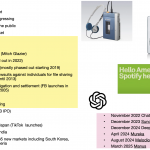

Are AI-powered music-generating and streaming platforms from China part of the next disruption? If we consider 1995-2005 as the “resistance era” against streaming (i.e., major labels clinging to physical media profits through very creative methods, in yellow below), perhaps we can consider 2005-2025 to be the “simmering period” of streaming consolidation. We are now witnessing the next paradigm shift led by AI-powered platforms (in pink below).

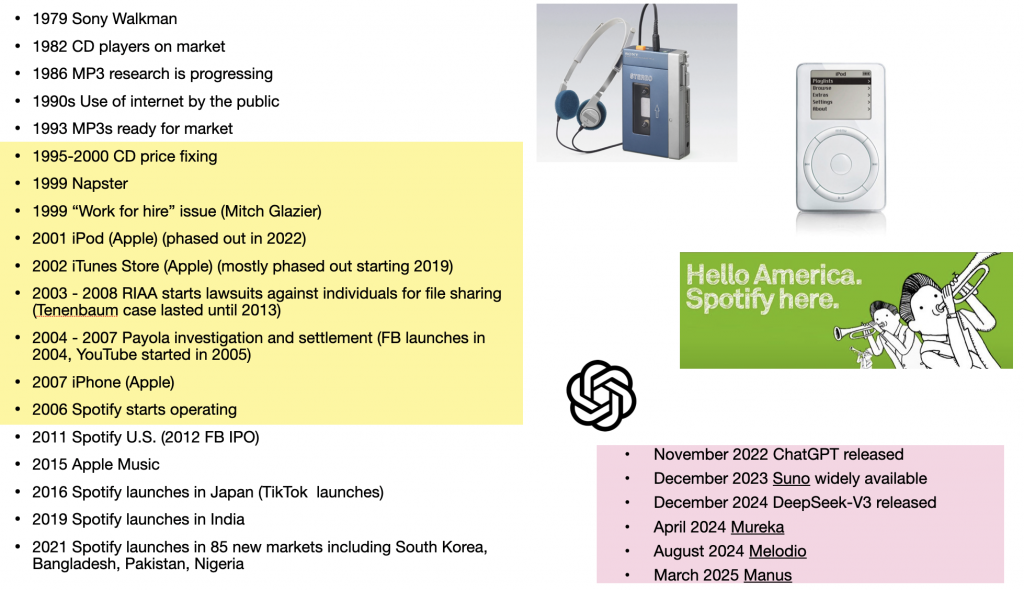

Of special note are Mureka and Melodio, developed by China’s Kunlun Tech, their calculated disregard for copyright fueling their ascent. Mureka’s advanced model can generate music from “reference tracks” which could be an uploaded track or a YouTube link, effectively crowdsourcing training data.

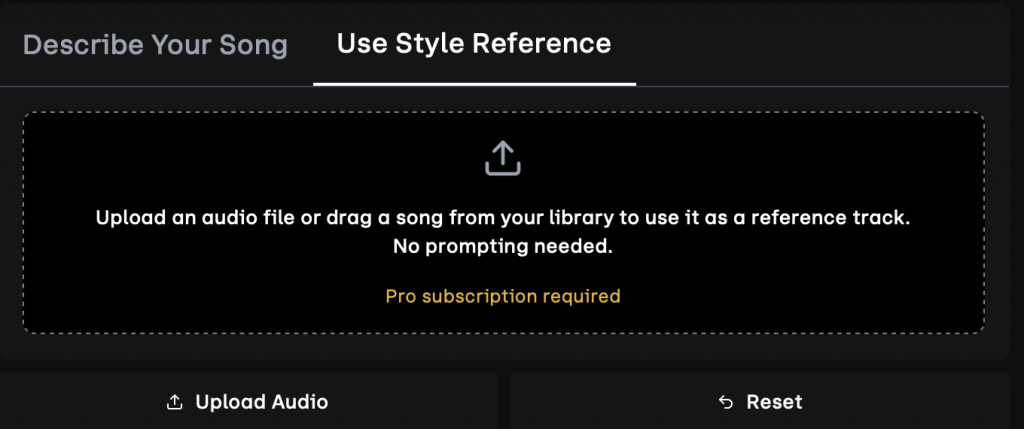

So, what happens to copyright in this case? I bit the bullet, subscribed to the “Pro” plan and proceeded to upload a track from my album. I did not encounter any content filters or copyright detection tools to stop me from uploading the track. Could I have uploaded a work that I didn’t have the rights to? If I’m not mistaken, at the very basic level, Mureka is asking for the user to become complicit in training the model in real time with copyrighted material.

To be fair, American AI-powered music-generating platform Suno and Udio have also been vague about training data and are currently being sued by multiple labels. 1 But they do not ask the user to upload tracks or use YouTube links as reference material.

Melodio seems to be more like Endel, a lean-back listening experience as the platform creates “an endless stream of perfect ambient music.” 2 This can further push the divergence of functional music from the rest of the recorded music output, allowing low-effort background music to be replaced by AI-powered music streaming platforms, reducing royalty payouts by minimizing human labor. Platforms can retain more revenue as production costs plummet. Again, copyright issues of its training data are currently not discussed.

How good are the Chinese AI-powered music models? Will they be popular? Regardless, at the very least, they are heating up the AI competition at the expense of rights holders.

OpenAI (now of Ghibli fame) has grabbed this moment to highlight the dangers of losing out to China. Regarding the White House’s development of an AI Action Plan3, OpenAI commented on March 13, 20205: “Applying the fair use doctrine to AI is not only a matter of American competitiveness—it’s a matter of national security. The rapid advances seen with the PRC’s DeepSeek, among other recent developments, show that America’s lead on frontier AI is far from guaranteed. Given concerted state support for critical industries and infrastructure projects, there’s little doubt that the PRC’s AI developers will enjoy unfettered access to data—including copyrighted data—that will improve their models. If the PRC’s developers have unfettered access to data and American companies are left without fair use access, the race for AI is effectively over. America loses, as does the success of democratic AI. Ultimately, access to more data from the widest possible range of sources will ensure more access to more powerful innovations that deliver even more knowledge.”4

But is “fair use” the right approach? On March 14th, RIAA commented: “Existing U.S. copyright law is sufficient to address copyright concerns arising from AI. In particular, our fair use doctrine…provides a manageable and nuanced approach to addressing liability for unauthorized uses of copyrighted works to train an AI system. As noted above, one court has already ruled that fair use did not apply to the type of AI training at issue in that case.”5

The rapid pace of development of AI-powered platforms around the world is challenging the music industry to reconcile technological progress with ethical and legal guardrails. If history is any indication, we are in for decades of chaos. In no scenario do I see the valuation of digital music increasing.

That said, there is enormous demand for music as a form of communication which fosters social bonding. From micro-events like themed house concerts to large-scale arena concerts, live music is booming. People want to get together. Fans want merch to show solidarity with their favorite artists as well as with fellow fans. Although it’s not always clear how all that translates to artists actually being able to make a living off of music, it’s still a very positive sign that music truly matters. Streaming is just one part of that eco-system.

4/12/2025: Editing to add that on April 1 2025, Udio also released a feature where the user can upload a reference track.

4/13/2025: Editing to add a link to AI 2027, prediction scenarios of AI impact written by Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander, Thomas Larsen, Eli Lifland, Romeo Dean. AI-powered music platforms fit right in.

- Tencer, D., & Tencer, D. (2024, June 24). Major record companies sue AI music generators Suno, Udio for ‘mass infringement’ of copyright. Music Business Worldwide. https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/major-record-companies-sue-ai-music-generators-suno-udio-for-mass-infringement-of-copyright/ ↩︎

- Melodio AI |Vibe Your Moment – Official website. (n.d.). https://www.melodio.ai/ ↩︎

- The White House. (2025, March 24). Public comment invited on Artificial intelligence action plan. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/02/public-comment-invited-on-artificial-intelligence-action-plan/ ↩︎

- OpenAI’s proposals for the U.S. AI Action Plan. (n.d.). OpenAI. https://openai.com/global-affairs/openai-proposals-for-the-us-ai-action-plan/ ↩︎

- Leibfreid, M. (2025, March 20). RIAA leads music community in AI filing – US creative leadership paves the way for innovation – RIAA. RIAA. https://www.riaa.com/icymi-riaa-leads-music-community-in-ai-filing-us-creative-leadership-paves-the-way-for-innovation/ ↩︎